In the ever-evolving world of technology, white-collar crime is an insidious and complex issue that permeates various sectors. Figures like Sam Bankman-Fried and Elizabeth Holmes have cast a shadow over the cryptocurrency and biotech industries, but they are not isolated cases. Fraudsters exploit technology’s allure, crafting intricate schemes that ensnare unsuspecting individuals, particularly vulnerable populations, like the elderly. Understanding these crimes requires an understanding of the broader implications of moral decay and ethical erosion within corporate spheres. The dizzying heights of financial success can quickly turn into moral abysses, revealing the detrimental effects of ambition untethered by integrity.

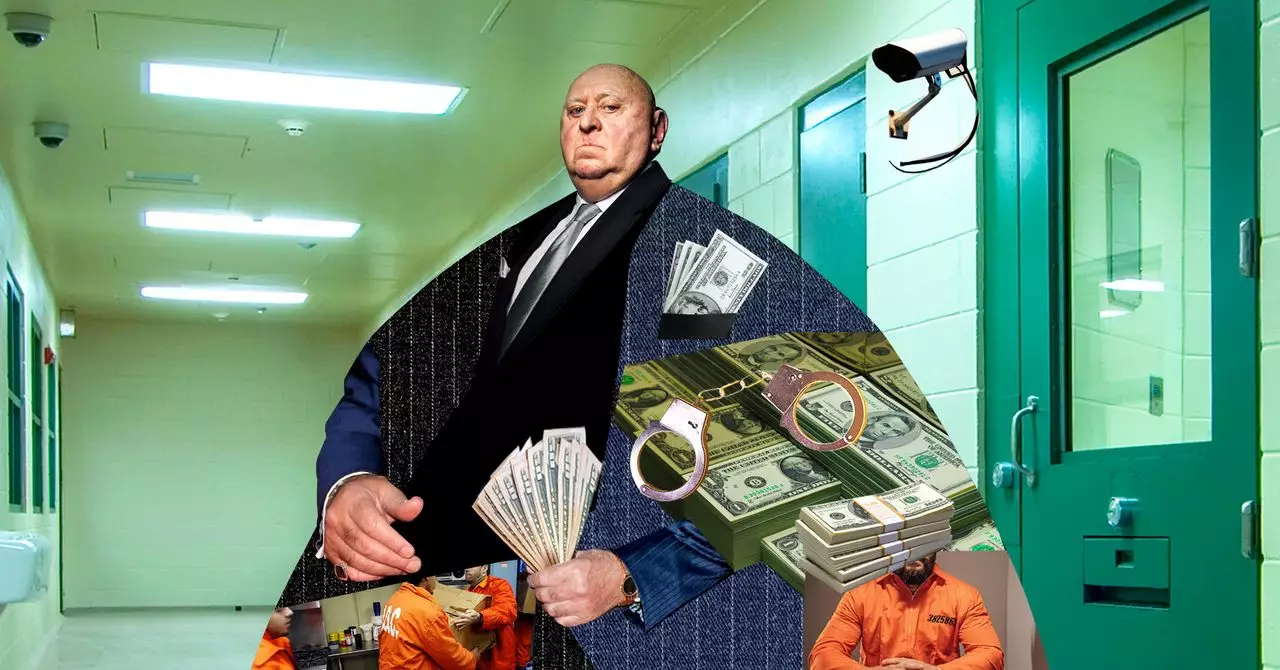

Behind these high-profile cases lies a lesser-known narrative involving a peculiar yet compelling figure: a former inmate who has turned his past misdeeds into a form of rehabilitation for those grappling with the aftermath of white-collar offenses. This prison consultant has an eye-opening tale, marked by both dark humor and startling revelations about the prison industrial complex and the broader societal implications of crime, punishment, and redemption.

From Inmate to Consultant: A Unique Transformation

The journey from incarceration to consultancy is both unconventional and enlightening. Our subject claims a history spent in correctional facilities, where he earned a reputation as a “troubleshooter.” His story does not merely illustrate an individual’s rise from the ashes; it unveils systemic issues within correctional institutions, where rehabilitation often takes a backseat to punishment.

In his own words, he describes prison as his “personal amusement park.” This notion may seem troubling, yet it points to a larger critique of the correctional system as a place that is more focused on containment than reform. Unlike many who fall into despair during their sentences, he found empowerment in manipulation and clever antics that allowed him to play the system’s intricacies to his advantage. It is this unique insight into human behavior that equips him with the tools to guide white-collar criminals through their own tumultuous journeys.

Helping the ‘Fearful and Confused’

This consultant’s clientele tends to encompass the “scared, angry, and confused,” individuals ensnared by the consequences of their choices. For him, the act of consulting is more than a commercial endeavor; it is an opportunity for advocacy and empowerment. Localizing his efforts within a burgeoning field where no one else was operating, he capitalized on an emerging market: offering guidance for those navigating the murky waters of white-collar crime.

The range of fees—ranging from a few thousand dollars to upwards of $50,000—illustrates both the value of his expertise and the varying financial circumstances of his clients. Some seek him out desperate for clarity, wishing to demystify their impending prison experience. Others may view his services through a lens of privilege, where financial means dictate access to support. Nevertheless, his mission seems steeped in a palpable sense of altruism that transcends transactional relationships, and he genuinely wishes to uplift others.

The Dichotomy of Crime and Morality

While it might seem paradoxical for a former inmate to champion the cause of white-collar offenders, there exists a compelling discourse on morality underpinning this transformation. The prevalence of white-collar crime raises questions: Who truly deserves sympathy, and who should face condemnation? The consultant does not shy away from these discussions. He provokes dialogue around the ethical underpinnings of our legal system, the societal excuses offered to wealthy offenders, and the often overlooked narratives of reformed individuals like himself.

In a landscape where crime can seem glamorous when associated with success stories like those of Bankman-Fried and Holmes, the consultant’s approach starkly contrasts this culture. His no-nonsense style serves as a reality check for would-be offenders, emphasizing accountability and the harsh realities of prison life without sugarcoating.

Rehabilitation or Exploitation?

The consultant’s existence raises important questions about the nature of rehabilitation and the ethics of consulting on crime. Is his business model one of empowerment, or does it tread a fine line of exploiting those who have already stumbled? The ethics of his services can be as murky as the motives behind white-collar crime itself. While his intentions may appear altruistic, it’s essential to reflect on the broader implications of commodifying rehabilitation.

The paradox remains: in a society where white-collar criminals often escape the same societal scorn as their blue-collar counterparts, individuals like this consultant navigate a complex ecosystem of moral ambiguities. They portray an altered narrative of what it means to turn from crime towards constructive elements of society, even while operating on the fringes of legality.