In the ever-evolving domain of technology, nostalgia often finds a way to intertwine with innovation. Dmitry Grinberg’s astonishing project epitomizes this blend, as he achieved the implausible: he managed to run the Debian Linux kernel, a software born in the 1990s, on an Intel 4004 microprocessor, which first debuted over 50 years earlier, in 1971. This feat is not just a mere curiosity; it embodies the intersection of creativity, technical prowess, and a love for computing history. Grinberg’s work prompts a reflection on what it means to push the boundaries of technological limitations and to celebrate the potential of retro computing.

The Intel 4004 is often regarded as the first commercially available microprocessor, yet it is almost laughably simplistic by today’s standards. With a mere 2,600 transistors, its capabilities are drastically limited—supporting only basic arithmetic operations and lacking hardware interrupts. This scarcity sets the stage for a monumental challenge. To coax the modern Linux kernel into operating on such an archaic piece of hardware, Grinberg had to employ unorthodox methods that many would deem improbable. The Intel 4004, while groundbreaking in its time, boasts a clock speed of only 790 kHz. It’s mind-boggling to consider that even an overclocked version remains firmly planted within the kilohertz range, presenting a major bottleneck in processing speed.

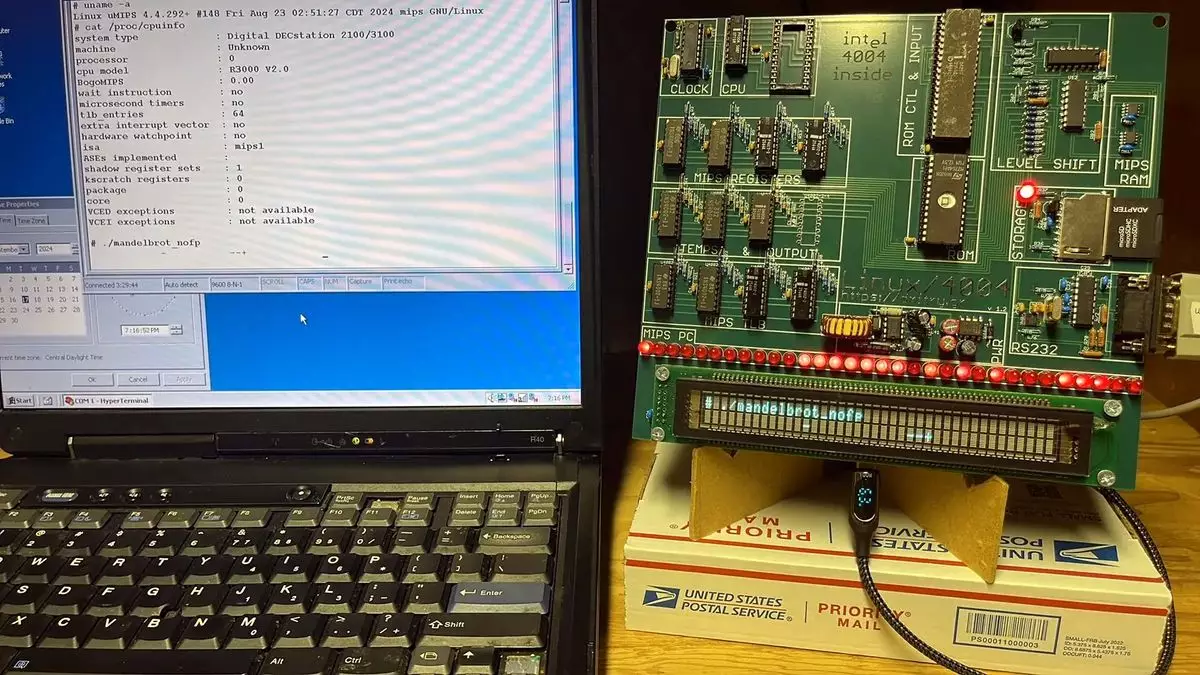

Grinberg’s solution to this archaic hardware limitation was a brilliant act of engineering. He avoided the impossibility of directly running Linux on the 4004 by creating an emulator to mimic the functionality of the MIPS R3000 processor. This emulation was particularly fitting since the MIPS architecture shares a temporal and conceptual relationship with the early versions of Linux. However, the implementation was no simple task; it required a cat’s cradle of custom circuit design, hardware emulation, and carefully selected components that respected the technological constraints of the original era.

This level of ingenuity demonstrates the creativity necessary to challenge what many may perceive as insurmountable odds in the realm of computing. By marrying ancient technology with modern software, Grinberg has not only resuscitated the spirit of innovation that marked the early computing revolution but also reignited discussions on what is truly possible in the field of retro computing.

Perhaps the most astonishing aspect of this venture is the boot time. Initial estimates for booting the Linux kernel were a staggering nine days. Such an expectation invokes a mix of disbelief and humor; could any reasonable person sit beside a laptop waiting for almost a week? Undeterred, Grinberg optimized his design, ultimately reducing the boot time to 4.76 days. This enormous duration beckons the question of practicality; however, this project has little to do with practical applications. Instead, it resides within the realm of artistic expression and intellectual challenge, celebrating the concept of what is possible when one boldly ventures into the unknown.

For viewers of the Linux booting process, a delightful visual is presented—the experience, captured on video, is fast-forwarded to accommodate the grand duration required. Such visual documentation serves as a reminder of both the old and new; we are able to witness history unfold through the lens of modern technology while simultaneously paying homage to the roots from which it emerged.

Grinberg’s remarkable achievement may not bear immediate functional benefits, yet it evokes profound admiration and curiosity. It stands as a testament to the impact of deep engineering knowledge, persistence, and an unwavering passion for technology. As the landscape of computing continues to evolve, projects like Grinberg’s remind us of the rich history that has shaped our current technological environment. They encourage future innovators to think out of the box and to consider that sometimes, the most significant breakthroughs may lie buried in the past. Indeed, one wonders what creative challenge Grinberg will tackle next. If the past is any indication, it might just be another iconic game, perhaps Doom running at a rate of 30 frames per month—now that’s a challenge worth anticipating!